USB Type-C, the supposedly magical new standard that promises to solve all our connectivity problems, is finally real and ready for mainstream use. Type-C has been in development for a while – we first heard about it over a year ago and first saw it in action at CES in January. Now, with the high-profile launch of Apple’s new ultra-minimalist MacBook, Type-C has gone public in a big way.

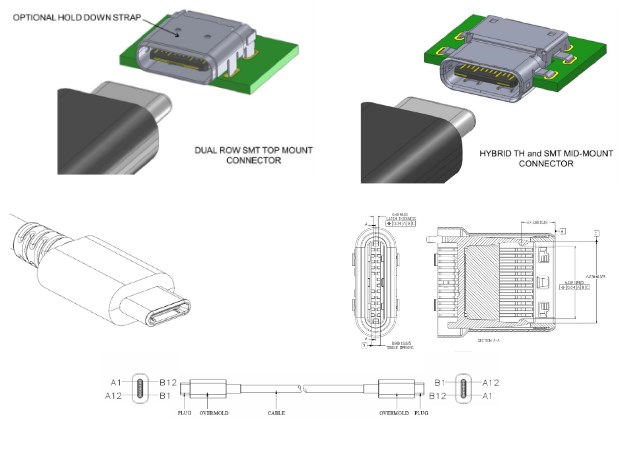

Type-C is meant to be able to work with all kinds of devices. More importantly, the same plug will be used on both sides of the cable and it is symmetrical so it can go in no matter which way is up. Users are often frustrated by USB plugs because they can’t tell with a glance which way they should fit. Type-C was designed with exactly that in mind.

But there’s a lot more going on under the hood, and there are going to be new problems. For starters, laptops can be charged using Type-C just like phones and tablets use USB today, but not all hosts will be able to deliver that much power. Type-C will replace dedicated HDMI, DisplayPort and VGA video outputs on many devices, but that doesn’t mean all devices with Type-C can be plugged into screens or projectors.

If you’re wondering what exactly this new standard means for you, we have all the answers.

The background

USB 1.0 and 1.1 ports first started appearing on PCs in the late 1990s and it didn’t take very long for the new standard catch on. USB provided an alternative to the mess of serial, parallel, PS/2 and MIDI ports a PC user typically had to deal with, but its most attractive feature was the ability to hot-plug devices. This meant that users did not have to shut down their PCs before making hardware changes, as had been the norm. Data transfer speed topped out at 12Mbps, which was enough for things like input devices and printers.

USB 2.0, which debuted in the early 2000s, raised the speed to 480Mbps, ushering in a whole new generation of storage devices and peripherals. This is when USB emerged as a viable standard for transferring data to and from devices such as portable media players and mobile phones. Battery charging was a natural extension, and so the standard evolved to improve power delivery. Experiments were made towards a wireless USB standard, but did not really go anywhere due to power requirements and limited flexibility.

USB 3.0 came out in 2008 in response to standards such as FireWire and eSATA that were better at high-speed bi-directional data transfers. Peak theoretical speed was raised to 5Gbps and for the first time, new cables and sockets were required. USB 3.0 ports and plugs were designed to be backwards compatible with older devices, which increased their size and cost to implement. However, there was no major disruption and users were not confused.

Less than five years later, USB 3.1 was released to double the peak speed to 10Gbps, using the same plugs and ports as USB 3.0. At this point the standard changed again, but not the connectors.

To make things a little more interesting, the label “USB 3.1” now applies retrospectively to 5Gbps USB 3.0 connections as well. The terms “USB 3.1 Gen 1” and “USB 3.1 Gen 2” are being used to refer to 5Gbps and 10Gbps implementations respectively. Apple, for instance, describes the 5Gbps Type-C port on its new Macbook as USB 3.1 which is technically correct but also somewhat disingenuous.

It’s impossible to imagine a world without USB – we would still have to depend on special-purpose plugs and ports for each kind of device. Charging devices, syncing data and transporting anything would be a nightmare of incompatibilities. In the age of USB, we have largely done away with installing drivers and rebooting each time we plugged a new device in to our PC – and if you can’t remember an age when this was the norm, consider yourself very lucky indeed.

Introducing USB Type-C

First of all, Type-C is not a new version of USB and does not replace USB 3.0 or 2.0. Type-C refers to the plug itself, and it is just a new possible interface for USB 3.1 (which now encompasses USB 3.0 as well). USB 3.1 will also be implemented with traditionally shaped USB ports and cables. Type-C will very commonly be associated with USB 3.1 but it is by no means guaranteed that a device supporting USB 3.1 speeds will use the Type-C connector, and vice versa.

Type-C will supplant the Type-A and Type-B connector types, which have until now been used to define the roles of USB host and target devices respectively. Standard USB cables were designed to have different connectors on either end to prevent people from doing things such as plugging one printer into another and expecting them to work without anyone sending print commands. Worse, people might have plugged two power sources into each other. It’s for this exact reason that power cables have always had different plugs on each end – and so such problems have rarely arisen, if ever.

Over the years, Mini-B and then Micro-B emerged to cater to increasingly smaller devices (more commonly known as Mini-USB and Micro-USB respectively). However, at the same time, devices once intended to be targets began to take on aspects of host devices. We wanted to be able to plug pen drives into smartphones, print directly from storage devices, and use touchscreen tablets as control surfaces, amongst other things. USB On-the-Go (OTG) allowed devices to host other target devices through their Type-B ports. However, dongles were needed because of the different port shapes, which meant the potential of the technology was rarely realised.

Now, we’ll be able to plug anything in to anything else. Theoretically, devices will sense each other and clearly establish what they expect of each other in terms of charging, control and data exchanges. Incompatible products just won’t work – people will still get frustrated, but hopefully not too much. In this sense, Type-C trades one set of problems for another.

Additional features and benefits

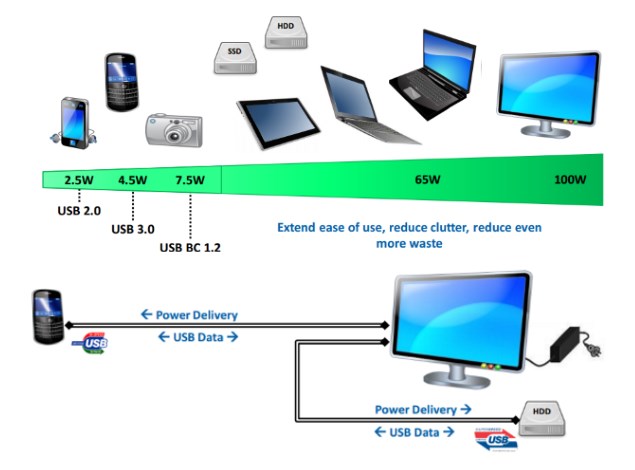

Beyond the potential bump up to 10Gbps speeds, Type-C allows for a whole raft of other features. The most important of these is the updated Power Delivery spec which allows devices to negotiate for up to 100W of power – ten times more than the 10W USB 3.0 was designed for. For desktop peripherals such as printers, this means separate power bricks could be dispensed with, and smaller devices will be able to charge a whole lot faster than they do now.

A single cable between a laptop or phone and a docking station could let the portable device send audio and video output and connect to networks and accessories such as hard drives and printers, while also receiving power. Multiple devices could be consolidated into one, reducing cable clutter. For example, Apple’s Thunderbolt Display already lets MacBook users do this with two cables – a possible future version with Type-C could reduce this to one. Eventually all kinds of desktop accessories could route power to our portable devices, and ports or card readers that can’t fit on devices themselves could be accommodated on the chargers we always carry around anyway.

Specific cables will be required for anything more than the basic 10W power level, for safety reasons. There are also larger implications, such as being able to run USB wiring around a house to eliminate the need for “wall-wart” adapters for charging small devices, but this is still a long way away.

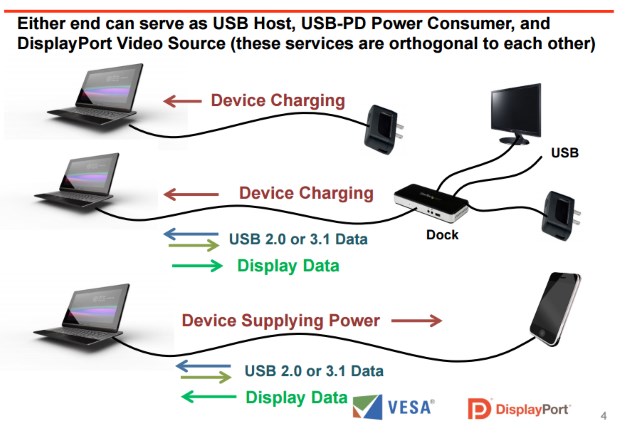

USB Alternate Modes will allow other protocols to ride over USB cables, potentially doing away with the need for their own ports and wires. HDMI, DisplayPort, MHL and DisplayLink are already on the list of supported standards, which means that devices supporting any of these modes will be able to work with each other through their USB ports, independent of USB traffic.

However, this there is going to be some confusion because of this. Having a USB Type-C connector is not the same as having a smaller HDMI port or DisplayPort built in, and doesn’t guarantee that a phone can be plugged in to a TV to play videos on it, for example. It is up to device makers to support any or all Alternate Modes, which they might or might not do for their own reasons. Users will have to understand which of their devices are capable of what.

The USB-IF has said it is working on “defining joint identification guidelines” that will hopefully help users know what they can and can’t do. Meanwhile, get ready to deal with an assortment of cables with USB Type-C on one end and HDMI, DisplayPort and various other potential mates on the other. Again, just being able to plug one device into another is no guarantee that they will work together.

The current state of affairs

Nokia’s recently launched N1 tablet uses a Type-C USB connector but you’ll only be able to achieve USB 2.0 speeds when transferring data between the tablet and a host PC or a mounted drive. There’s no indication of whether it supports quick charging or any of the Alternate Mode features.

Motherboard manufacturers such as Asus and MSI have announced a raft of USB 3.1 refreshes, but very few models have the Type-C connector. Most feature two Type-A ports but again, there are caveats. They both branch off the same controller and so they share bandwidth – you’ll only be able to get the peak 10Gbps if you don’t use both ports at the same time . You’re also limited by the motherboard itself, and the amount of PCI-Express bandwidth available internally to the controller.

You also won’t be able to charge laptops from these ports because motherboards simply aren’t designed to route that much power around – to do this, some kind of bracket or adapter would be needed with its own feed from the PC’s power supply. Of course the power supply itself would need to have enough overhead to push out an extra 100W of power on demand, and this is an area in which cost-sensitive PC makers are not known to be generous.

The new Chromebook Pixel (2015) features two Type-C ports and you can use either one for charging and/or to charge smaller devices. Both ports will also allow DisplayPort and HDMI video output using adapters, according to Google. The device ships with a 60W charger but it will charge slowly from 10W USB power sources. Incidentally, Google has promised widespread Type-C support on future Nexus products and other devices.

You could plug two Chromebooks into each other, but since devices are supposed to negotiate the amount of power they need when compatible sources are plugged in, we have no idea how that would work out.

And then of course there’s the shiny new MacBook. If any device is really going to push Type-C into the mass consciousness, it will be this one – it has a single Type-C port and no others. The new MacBook comes with a 39W charger and a cable with Type-C on both ends, but guess what? The cable will work for data transfers only at USB 2.0 speeds.

Apple is calling the port USB-C, which is bound to catch on. This might cause some confusion because it implies a new version of USB. However, Apple says the port supports “USB 3.1 Gen 1 (up to 5Gbps)” which, as we know, is no better than the speed of good-old USB 3.0.

If you want to plug anything else into your MacBook, you’ll need an adapter. Apple has already listed two, each of which breaks out into one Type-C port, one Type-A port, and either HDMI or VGA for video output. Each one costs $79 (approximately Rs. 5,000) and a simple USB 3.1 Type-A adapter costs $19 (approximately Rs. 1,200) – and Apple being Apple, you don’t get any of them in the box even when you spend up to $1,599 on a new MacBook.

The future

Thankfully USB (in all its forms) is an open standard and other companies will soon be selling similar accessories for much less. We expect to see dozens of USB Type-C devices from pen drives and HDDs to dongles, adapters, hubs, docks and chargers announced by mid-2015. SanDisk, Adata and LaCie are amongst the first to have announced products.

However, devices that rely on Alternate Mode functionality will simply not always work as you imagine they should. You’ll want to check specific device compatibility rather than relying on USB Type-C as a standard.

Multi-interface devices will probably be popular for a while, as Type-A and Micro-B aren’t going to disappear for at least another decade. And while Type-C adoption will hopefully be very quick, smartphones are unlikely to switch over from Micro-B in the immediate future. It took long enough for all the world’s manufacturers (but one) to standardise on Micro-USB, and with laws in place in the EU and other parts of the world, change will not come quickly.

Meanwhile, other port standards such as Thunderbolt are likely to die out. Apple was really the only company that ever put much muscle behind it, and high licensing costs combined with a lack of appeal compared to USB 3.0 never let it gain much momentum. Additional USB ports would be more than welcome on the next revisions of all Mac hardware, and we don’t think anyone would mourn Thunderbolt for very long if it quietly went away.

Many devices could ditch their single-purpose ports such as HDMI and Ethernet. With cheap universally compatible adapters in wide circulation, slim devices wouldn’t have to sacrifice connectivity anymore. Docking stations could become popular in schools and public spaces, turning our phones or other portable devices into full-fledged workstations with a single wire.

For that matter, all our lives would be considerably improved if Apple replaced its proprietary Lightning interface with USB Type-C – though the company isn’t likely to give up its margins on accessory sales anytime soon.

The USB Type-C connector will solve a lot of problems for a lot of people, but it will also create a few new ones in the short term. We can only hope that Type-C will last through the next few USB speed revisions and we won’t have to deal with another connector type for a very long time.